Fraidy Reiss was still a teenager when her family, part of an insular, tight-knit religious community, forced her into marriage. The relationship lasted eight years and included beatings, verbal abuse and misery.

Because of her and fellow advocates, there may be fewer child brides in the future.

And that's a good thing, those advocates say. Currently, in 25 states, there is no limit to how young a child can marry, if a judge permits it, according to the Tahirih Justice Center, a nonprofit advocacy group. There are tens of thousands of women and girls in this country who got married under 18. Many were not forced. But few of these brides live happily ever after, Reiss says. They are far more likely than older brides to end up bruised in domestic-violence relationships, as well as impoverished, undereducated, more sickly—and divorced.

"Age at marriage has for decades been the strongest and most unequivocal predictor of marital failure," wrote Vivian Hamilton, a legal scholar at William & Mary Law School in a 2012 research paper on child marriage. The likelihood of divorce nears 80 percent for those who marry in mid-adolescence, then drops steadily.

Between 2000 and 2015, well over 200,000 children under age 18 were married in America. That's according to a 2017 research report, by the Tahirih Justice Center, that outlines the legal picture of U.S. child brides, state by state. Some 57,800 minors ages 15 to 17 married in 2014, the majority of them girls, according to a 2016 report by the Pew Research Center.

The children involved are predominantly from rural areas in the South and West, says Hamilton, and of those, many tend to come from poor, less educated and conservative religious backgrounds (mostly Protestant and fundamentalist Mormon). Many get married because they want to have legal sex, or because their parents want to legitimize a pregnancy. Or because marriage would make a statutory-rape prosecution for the man go away, among other reasons.

Critics of child marriage see baffling things in some state laws. Half the states have no age limit for marriage. And in many states, they say, the legal age of consent for sex doesn't match that state's legal, permissible age for marriage. Advocacy group Human Rights Watch, for example, has pointed out that until New York changed its child-marriage law last year, 14- and 15-year-olds could marry, with permission of a judge and parent.

"Marrying as a child creates devastating lifelong consequences," said Reiss, whose New Jersey-based "Unchained at Last" nonprofit advocates for women and champions changes in state laws regulating marriage. Child marriage harms lives, even when the marriage is not forced, as hers was. "We know women in their 40s who are still trying to dig out," Reiss said.

For her part, Reiss rebelled at 27, divorcing her abusive husband and shrugging off how her own family shunned her to this day: "I'm still dead to them." But at age 32 she was the valedictorian speaker at Rutgers University's commencement. Forbes named her one of Five Fearless Female Founders to Follow in 2018. She started Unchained four years ago.

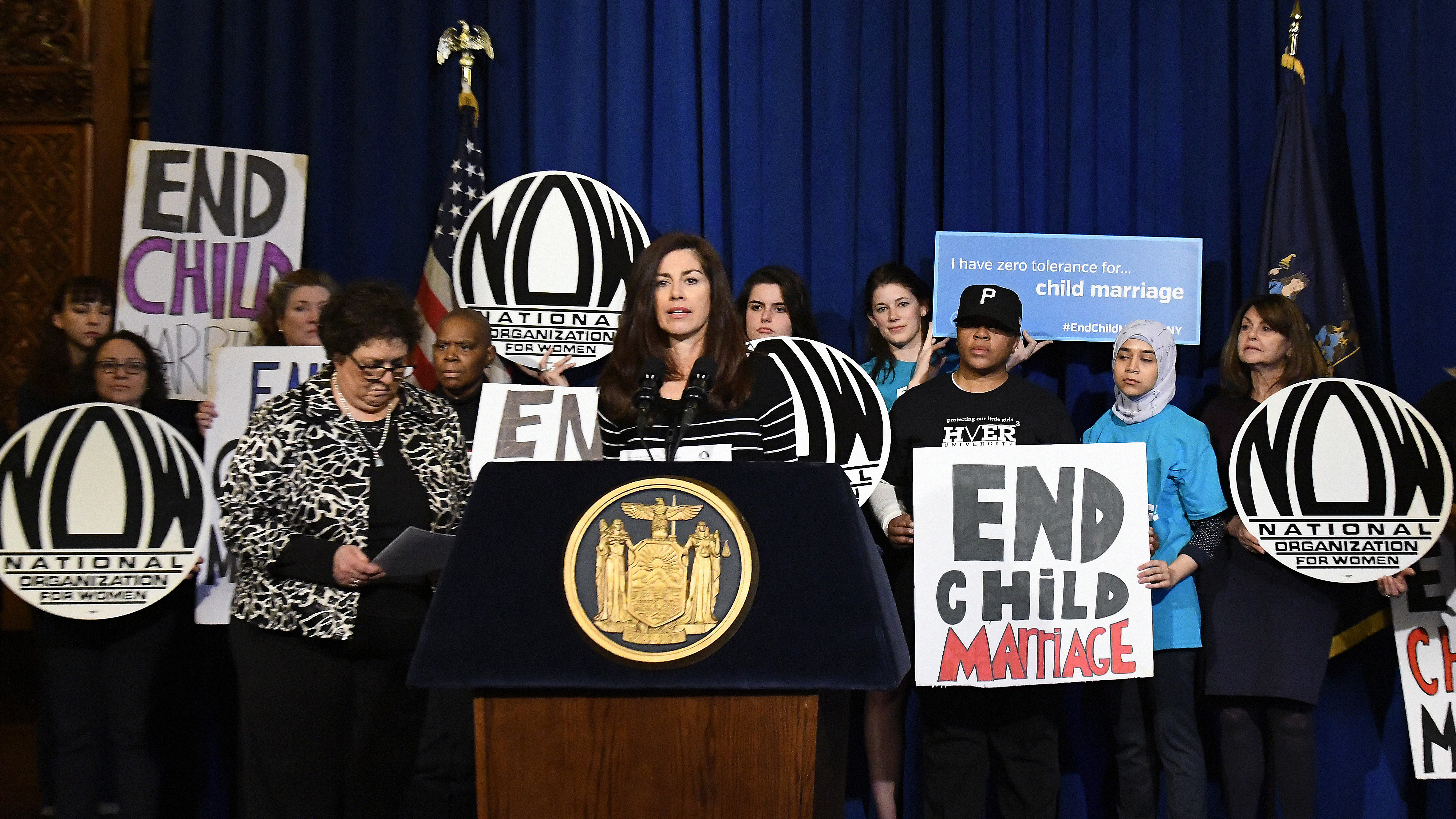

Today, says Nicholas Syrett, an historian and professor at the University of Kansas, there's a national movement gaining traction across the country to raise the minimum legal age of marriage. New York last year prohibited all marriages before the age of 17 and permits 17-year-olds to marry only with a judge's permission. Texas and Virginia recently passed similar laws. "And that movement is happening mostly because of organizations like Unchained At Last, and the Tahirih Justice Center," Syrett said.

How we got here

In his book "American Child Bride: A History of Minors and Marriage in the United States," Syrett writes about the origins of child marriage in the U.S., calling it an evolving holdover from our social history.

It's hard to quantify how many child brides there used to be, since record-keeping in previous centuries was spotty, and many people fudged their true youthful age. But child marriages have declined from the past, Syrett said.

"Before the 20th century, people didn't pay nearly as much attention to age as we do now," he said. "A lot of people didn't even know their own birth dates. Many children back then did adult things, before we passed child-labor laws. So you had not only child brides, but children working in factories."

"That's not the world we're living in now," he said.

While many people entering child marriages today are carrying on traditions, religious and social, it's hard to research the whys of child marriage, Syrett said. "It's not like clerks at the courthouse ask you why, when they give you the marriage licence," he said. "They just ask how old you are."

While some of these marriages are forced or arranged, most aren't, he said. "Some marriages are coerced, by parents, for religious reasons," he said. "But I suspect it's often more about attitudes about sex. It's clear that in some southern conservative states, young couples want to have sex legitimately, and marry. So in that sense, many of these marriages are made as relatively informed decisions."

In some states, prosecutors of crimes will not prosecute a man for statutory rape, if the man marries the girl involved.

'A well-meaning place'

There's no real black-and-white line between villains and victims, though.

The biggest surprise Hamilton encountered, after she researched child marriages, is how vigorously many state legislators resist raising the minimum marriage age. That baffled her—until some of those legislators called to ask her advice about the laws.

She thinks they are wrong to resist raising the legal age. "But their hesitancy to change the laws, I think, comes from a well-meaning place. One legislator told me how a young man from his district was being deployed in the military, at the age of 18, and that he wanted to marry his girl, who was 17."

Some legislators have a religious constituency, and are sincerely trying to reflect the beliefs of their constituents, Hamilton says. "As a legal scholar, I don't have a constituency, so it's much easier for me to say we ought to raise the age."

Many of the children who enter these marriages, along with the parents and legislators who support them, often do so because they view it as the lesser of evils, Hamilton and Syrett said.

They'd rather the girl marry—hoping the man will support the girl and unborn child. Or they'd rather the girl marry than give birth to an illegitimate child. Or they'd rather the male involved will support his child wife instead of serve time in jail for statutory rape.

Then there's abortion, Syrett said.

"Legislators don't want them to consider pregnancy termination as an option," he said. "There's no evidence the girls involved would do that, but that's the worry of some of the legislators."

The legal picture

Advocates are working to persuade those legislators. In 2016 Virginia, heavily lobbied by Unchained and the Tahirih Justice Center, became the first state to limit marriage to adults age 18 or older, with a narrow exception made for court-emancipated minors given full adult rights.

Texas and New York in 2017 passed bipartisan bills into law, limiting marriage to legal adults, and putting in safeguards preventing forced marriages. Legislators in dozens of other states are considering new laws, including in Kentucky, California, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Hampshire, New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Reiss and her fellow advocates will keep working on this, she said.