Adolescence can be bumpy, even for the otherwise well-adjusted: Your body is changing, your homework is intensifying and the unofficial entrance exams to adult life—your driver’s test, your first alcoholic beverage—arrive at a seemingly unrelenting clip.

Imagine, amidst all that chaos, finding out that your father had strangled more than half a dozen women to death.

That’s the situation Melissa Moore found herself in one spring day in 1995, during her freshman year at Shadle Park High School in Spokane, Washington.

“People still wonder, ‘How did you not know?’ ” Moore says. “Serial killers, they carry the mask of sanity well.”

That mask came off abruptly when her mother sat Melissa and her two younger siblings down at the kitchen table and delivered some disturbing news.

[Watch Monster in My Family: Happy Face Killer: Keith Hunter Jesperson on A&E Crime Central.]

“She said, ‘Your father’s in jail,’ ” Moore says. “She wouldn’t give the charges at first. My brother demanded an answer and she [finally] said, ‘For murder.’ We didn’t know it was for serial murder. And then it was just a floodgate: all these new charges, all these new cases.”

Moore’s father, Keith Jesperson, was a truck driver living a double life.

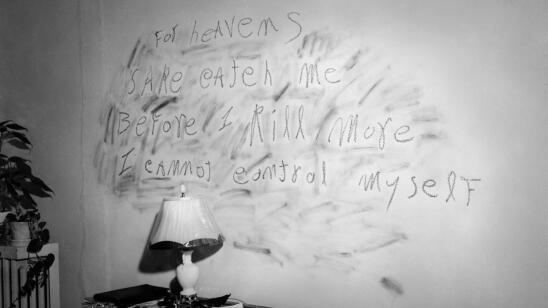

In young Moore’s eyes, he’d always been a benign and loving patriarch: taking her to town for ice cream and gummy worms, offering to gift her a Pontiac Grand Am so she could have her own wheels. But on the road, Jesperson was targeting women—mostly sex workers—and sending letters detailing his deeds to local media, signed with a smiley face.

That behavior earned him his “Happy Face Killer” moniker, and today, Happy Face is serving three consecutive life sentences without parole at Oregon State Penitentiary. Eight of his killings are confirmed. He claims to have murdered dozens more.

As details of the cases came in, Moore’s mother refused to divulge details to her shell-shocked children. Now a mother herself with two daughters, Moore says she still disagrees with her own mother’s judgment from the time, but has come to sympathize with it more: “I can’t imagine how my mom, hearing that news, had to give that news to us,” she says.

Undeterred by her mom’s reticence to share information, Moore would go to the city library and scan microfiche of newspaper articles where she would learn details of her father’s ongoing trial.

“That was really difficult,” she says. “I was reading quotes from the families of victims. And their grief and their heartache and anger…to hear them calling my father a monster—that was a new situation to be in. At the time, he was my beloved father.”

Moore says she and her siblings splintered despite their shared nightmare, each dealing “with grief in our own way” and in “survival mode.”

At school, Moore was ostracized by her peers. She finished out the school year and then transferred to a new high school before 10th grade. When word of her father’s acts spread around her new school, she transferred again.

But even when she was able to successfully hide her past, her ability to connect was impeded.

“I felt guilty by association,” she says.

Some of this guilt was tied to her inability to detect her father’s criminality, she says. Memories flooded back to her in the wake of his arrest—of seemingly jokey campfire confessionals, or offhanded remarks made while driving by a ravine where a body had been dumped.

In her adulthood, Moore has come to accept that she had an inherent blind spot as a young daughter that would’ve made spotting her father’s crimes nearly impossible. To this day, however, she wonders why some of her adult relatives didn’t think more of her father’s penchant for torturing animals.

Moore says that when she was a young girl her family lived in rural Washington, and that she would leave milk or food out for stray animals that would come onto the property.

One incident, in particular, is burned into her memory. “A cat walked by while he was working under the sink, and he stopped what he was doing and he strangled the cat,” says Moore. “There was blood everywhere. I was screaming.

“I don’t recall how my mom reacted.”

“[Relatives would say], ‘that’s just Keith. That’s just him,'” Moore says. “But that’s just rationalizing or dismissing really sadistic, horrible behavior. Sometimes I think about what they knew then.”

Like Moore, many of Jesperson’s adult relatives were also ostracized after his arrest, although their problems were financial as well as social. As word got out, colleagues and clients would end working relationships with members of her family.

“You hear the saying: ‘The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.’ It’s just the consensus of the public, and it’s not true, but it’s the mentality they treat you with,” she says.

It’s also a mentality that Moore admits to grappling with herself. Concerned that her father’s homicidal sociopathy was at least partly due to genetics, Moore says, “There was a season in my life where I was a new mom when that was more of a concern that was built in my mind. What was the likelihood I could perpetuate another criminal? How much am I like my dad?”

Moore has since written two memoirs about the topic: Shattered Silence and Whole, the latter also a self-help book for those struggling to recover from trauma. She also works as a crime correspondent for The Dr. Oz Show, helping interview families of murderers and victims. And she’s not the only one in her immediate family devoting her life to a professional reckoning with her father’s legacy. Today, Moore’s mother is a social worker who helps women transition off the streets into permanent housing. Her sister is an E.R. trauma nurse.

As for the father-daughter bond, Moore and Jesperson had so long ago, she says the two are no longer in communication.

Pressured for some time by her grandfather (Jesperson’s father) to remain in touch, she finally cut off contact in 2005, at the age of 26. She says his deeds (and her mother’s subsequent secrecy in dealing with the aftermath) have fundamentally informed the way she parents: from a position of radical openness.

Moore hopes parents who have the misfortune of finding themselves in her mother’s shoes will do the same.

“If your child asks you a question, respond to the question,” Moore says. “My daughter’s original question was, ‘Where is your daddy?’ I said he lives in Salem. The questions progressed as they got older. A child won’t ask for something they’re not ready for.”

As she sees her daughters growing up, Moore says that the enduring stain of her father’s behavior continues to anger her in new ways, for their sake.

“My children can’t outlive his name,” she says. “When people ask about their grandparents, which mostly comes up during the holidays…it’s a topic they have to avoid. But we don’t call him ‘Grandpa’ in my family. When we talk about him, we call him ‘Keith.'”

Related Features:

Serial Killer BTK’s Daughter Kerri Rawson: ‘We’re All Trauma Victims’

‘It Absolutely Broke Me’: What It’s Like to Befriend a Serial Killer

The Happy Face Killer and 7 Other Killers Who Left Notes

‘Good Luck Sleeping Tonight’: Serial Killers Plague Most Cities