It’s no big surprise that TV crime dramas often take some creative liberties with how crime scenes are portrayed.

We asked Ken Martin, a 33-year veteran of the Massachusetts State Police who retired as the commanding officer of the Crime Scene Services Division, about the accuracy of some of the procedures we’ve seen on dramas.

Has the forensic field become more popular recently?

Years ago, no one wanted to come into this [field] because you had to go to the death scenes. Sometimes people had been there many days, even if they died through natural means. Then, with the whole CSI thing, it exploded to where everyone wanted to be a crime-scene investigation expert. Some of the films or TV shows try to make it as realistic as they can. For example, I was contacted on the film Mystic River about what type of clothing we wear at crime scenes.

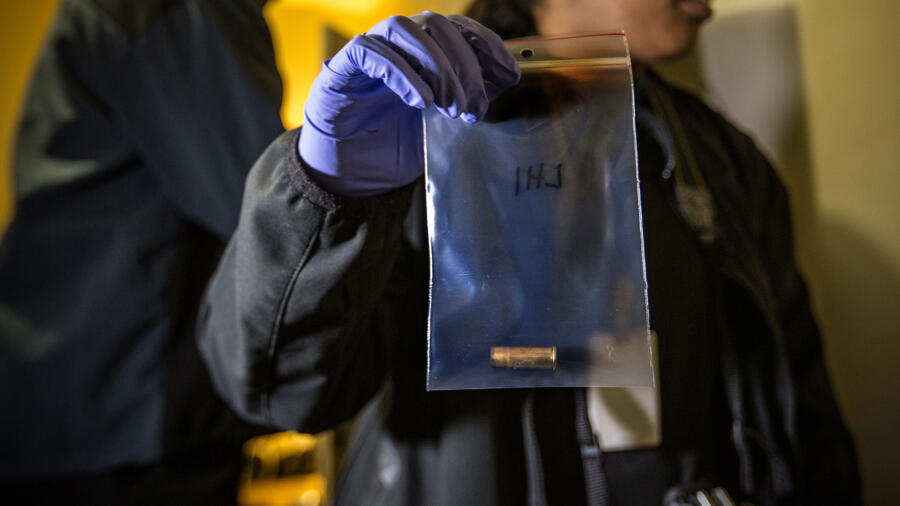

What do you think when you see a TV crime-scene investigator digging a bullet out of wall with a knife and popping it into a bag?

We would never use a knife to cut a bullet out from a wall. You can plot the bullet’s trajectory, or its path. So, if I look at the hole in the wall—and maybe I have a corresponding hole further into the wall—that gives you two points, which gives you a straight line. Sometimes you create a line with a laser to envision the path of a bullet. Then you can go back and reconstruct it. I could potentially project back to where the round was discharged from. To just cut the bullet out of the wall, that’s [losing] a very important piece of data that could actually indicate where the shooter was.

In some TV shows they’ll have red strings radiating out from where a body was at a crime scene. Is that real?

That’s called stringing a scene. I teach at quite a few schools and we teach that in class; it’s one of things you need to do [as a crime-scene investigator]. But, there are two computer programs that currently do that. It’s called convergence. If I properly document those little strings, it’s going to give me what’s called impact angles. If I gather the necessary data and plug it into the computer, it’s going to give me the coordinates of an area of origin. If I properly photograph it, instead of stringing it, I can do it mathematically on the computer.

Many times, [the scene is] a drug area with blood that is contaminated with hepatitis C and other things. So, I’m very reluctant to kneel down on the floor stringing strings in an area because of biohazards. If you take a really good photo of a tiny little stain, you can enlarge it back at the office. Now, I’m sitting at my desk enjoying a cup of coffee in the air conditioning and I can calculate an impact angle and not worry about biohazards.

Is fiber evidence as foolproof as it seems on TV?

I don’t know about foolproof, but you have to understand that this type of evidence deals with uniqueness. I’ve had this happen in a case: A girl’s body was dropped off in a blinding snowstorm after being murdered. On her body, we recovered nylon, rayon and jute fibers. Now, we found out what cars had that combination of fibers in their carpet or upholstery. We contacted the maker; it was a Chevrolet, I believe. We found out what years this particular carpet was used and how many were on road. Then the investigators went to the Registry of Motor Vehicles or DMV [to find out] how many were in this part of the state. It turned out it was a very late-model vehicle; there were not a lot of them on the road. Can fiber evidence have value when you start to look at probabilities or likelihood? Yes, ultimately, we seized the vehicle.

What about shoe impressions?

I had a very sad case: A girl was home from college for Christmas vacation visiting her father. She had a younger sister. The sister goes out to a New Year’s Eve party. The mother and father go out. She’s left alone.

An individual happened to get thrown out of a party and passed by. He sees her watching TV and breaks in and kills her. There was snow on the ground. There were footwear impressions that we were able to cast in the snow. The police developed a suspect. When they go to his house, we tell them what type of shoe outsole we are looking for. They recover some shoes that appear to match and bring them into the lab.

In the lab, the outsole appears to match the shoes, which were fairly new so there were no characteristic marks. He hadn’t worn them and made cuts and dings. What we normally do, depending how tenacious you are in your investigation, is we call the shoe manufacturer’s corporate office and discuss the case. As luck would have it, that shoe company told us they conduct these meetings with designers who make, say, 12 prototype pairs of shoes. The designer brings them to a meeting and presents the prototypes. They get a thumbs up or down. If it’s down, they have these extra pairs of shoes and there are no other shoes like them in the world. What are the chances? But in this case the designer gave a unique pair of those prototype shoes to this kid.

Do the shows ever reveal techniques you would prefer stay under the radar?

Sometimes it is a problem for us when shows like CSI use some of the new, innovative techniques we have, because [it] is one of the most highly- watched shows in correctional facilities. For example, we started to have the ability to develop latent fingerprints inside latex gloves. If this was used in an episode, the criminals [would] start [taking] their gloves with them instead of leaving them at scene.

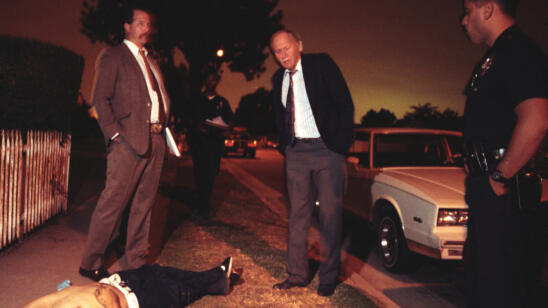

Where else do you see the TV dramas getting it wrong?

In my classes I [show] a slide in that I pulled from the original CSI series. David Caruso, aka Horatio Caine, and a female agent are in the photo. They are standing together and he’s holding tweezers with a piece of evidence in it. He’s looking at it, but he’s wearing dark glasses. She’s holding a flashlight on it.

I ask the class: What’s wrong with this photo? They say, ‘If he took the damn glasses off, he wouldn’t need a flashlight to see evidence.’

Read Part 1 of the interview: Why It’s OK to Leave Dead Bodies in the Woods, and Other Strategies for Not Messing Up A Crime Scene

Read Part 2 of the interview: It’s Tough to Get Fingerprints in the Winter: Challenges and Surprises About Crime Scene Investigating

(Image: Evelyn Hockstein for The Washington Post via Getty Images)