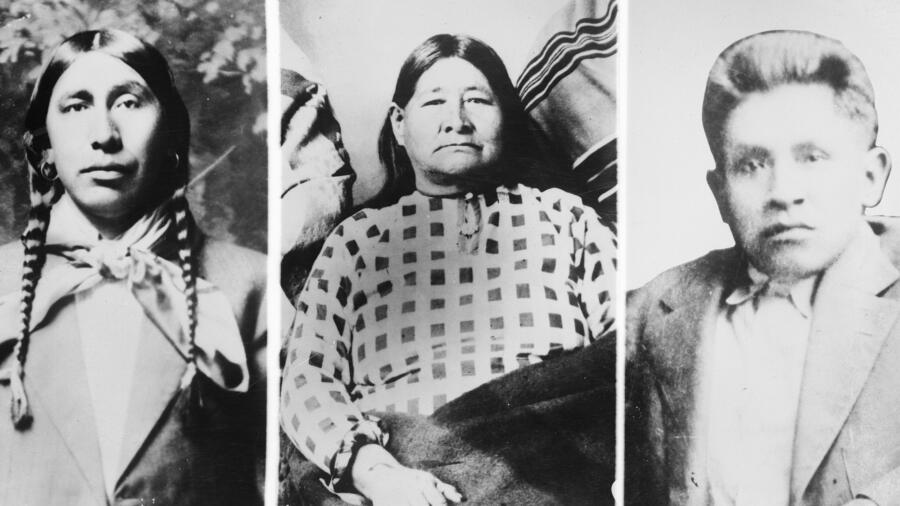

Three victims of the Osage murders: Henry Roan, Lizzie Q., and Charles Whitehorn. (Image: Getty Images)

A weekly look at the best new crime, suspense, and detective writing. Remember to read with the lights on.

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI

By David Grann

This fascinating book by the author of the bestselling The Lost City of Z delves into how the Federal Bureau of Investigation became the agency we know today. Grann goes back to Oklahoma in the 1920s. Despite having only been a state for two decades, this rocky patch of soil was home to the richest people per capita in the world. The Osage Indian nation had been pushed by the U.S. government onto this seemingly undesirable land. Turns out those rocks were on top of vast seas of oil.

It was still the Wild West, with oil men named Getty and Sinclair and Phillips making their fortunes. Under the Osage Allotment Act of 1906, all the subsurface minerals within the Osage Nation Reservation (now Osage County) were owned by the tribe but held in trust by the U.S. Government. In 1923, the height of the boom, oil gushed out of the ground and the tribe earned more than $30 million in revenue. The Osage were considered by the government to be too unreliable to manage their own affairs and were assigned guardians for their fortunes. Grann writes about how some had to ask permission for even minor expenses.

The royalties from mineral leases were paid to the tribe as a whole, via a hereditary share, or “headright.” On the death of an allotted tribe member, the headright would pass to the next legal heir who (before a 1925 federal law) did not have to be Osage to inherit.

That got some people thinking nefarious thoughts.

Mollie Kyle was an allotted full-blooded Osage married to a non-Indian man, Ernest Burkhart. Mollie began losing relatives with frightening speed. Her mother Lizzie, who had four headrights—three inherited—began to waste away and died in 1921 (poison was suspected). Lizzie’s daughter Anna Brown was found shot to death beside a river in 1921. Another daughter, Rita Smith, was blown to smithereens (along with her husband and a housekeeper) in 1923 when someone planted a bomb in her Fairfax, OK, home. All these headrights went to Mollie—and her husband Ernest. Then Mollie, feeling ill, suspected she was being poisoned, too. Along with the losses in this one Osage family, there were some 24 other deaths. An attorney gathering info on the crimes was thrown from a train. An oilman friendly to the Osage went to D.C. to try to get help. He was found the next day stabbed 21 times with his head bashed in.

The Osage Tribal Council turned to what was then called the U.S. Bureau of Investigation and its young director, J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover recruited a former Texas Ranger named Tom White, along with John Wren, one of the first Native American agents, to head an investigation. They followed the trail back to Ernest Burkhart and his uncle, William K. Hale, and John Ramsey, a local farmer/cowboy. Their trials captivated the nation. Grann skillfully tells the exhaustively researched origin story of the federal agency that’s still making headlines today.

A&E’s True Crime gets closer to the people and the stories behind the crime headlines.