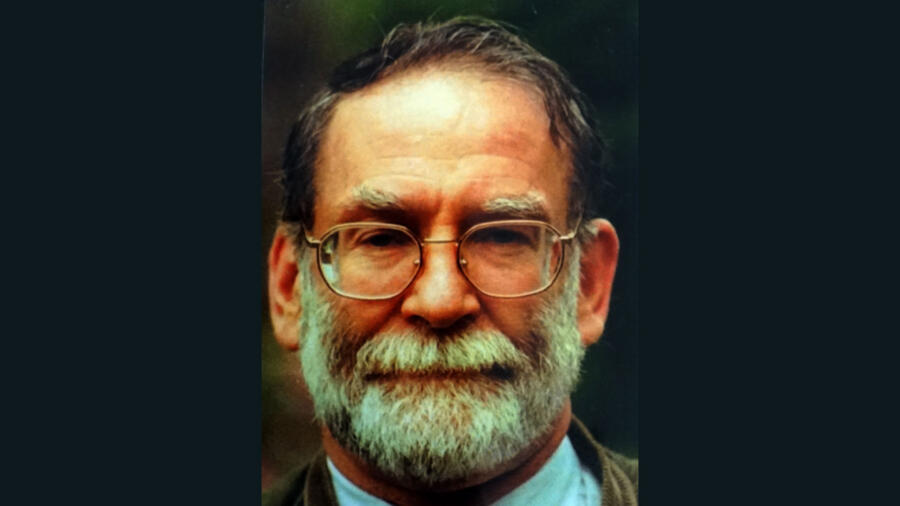

In 1998, patients flocked to 52-year-old Harold Shipman, who had a thriving medical practice in Hyde, a suburb of Manchester, England. But in September of that year, Shipman was arrested for killing one of his patients. The subsequent investigation revealed that this doctor and married father of four was one of the most prolific serial killers in history.

An official inquiry found that Shipman killed at least 215 of his patients while working as a general practitioner between 1975 and ’98, and suspected his involvement in 45 more deaths. The inquiry later looked at Shipman’s actions after he graduated from medical school in 1970 and found another 24 suspicious deaths dating back to 1971, which brought his suspected victim count to 284.

A&E True Crime takes a look at Shipman’s life and crimes—what motivated him, how he murdered his patients without getting caught and what finally brought his killing spree to an end.

Why Did Harold Shipman Kill His Patients?

One theory is that Shipman’s murders were tied to his mother, who died of cancer when he was a teen. Before she passed away, doctors gave her morphine for her pain. The official inquiry noted that Shipman’s preferred method of murder was to inject a patient with a deadly dose of diamorphine while visiting them in their homes. And among his confirmed 215 victims, 171 were women.

However, Phillip Shon, a professor of criminology at Ontario Tech University, cautions against reading too much into who Shipman chose to kill. “I would conjecture that he was shaped by access to victims,” he tells A&E True Crime via email. “Had he worked in an infant ward, I would conjecture that his victim selection may have been different.”

Beatrice Yorker, professor emerita of nursing and criminal justice at California State University, Los Angeles, is an expert in medical serial killers who tracks and catalogs their behavior. She tells A&E True Crime, “Our database is up to 150 health care providers, worldwide, who have been prosecuted for serial murder of their patients.”

“We have several categories of healthcare serial killers,” Yorker says. “We have the attention seekers…healthcare serial killers who do it for the thrill of rescuing patients in a code. But since [Shipman] had no witnesses, and he wasn’t trying to impress his colleagues in the hospital setting, he’s more in the power and control category.”

The official inquiry notes that Shipman’s patients felt he was a compassionate doctor and appreciated his house calls.

“His way to control them was to endear [himself to] them,” Yorker says.

How Shipman Killed for Decades

Later nicknamed “Angel of Death,” “Doctor Death” and the “Good Doctor” in the press, Shipman might have ended his killing spree in the 1970s. In 1975, he was caught forging prescriptions for pethidine, an opioid he was addicted to, and lost his job at a West Yorkshire medical practice. Yet, after a stint in rehab, Shipman got the chance in 1977 to resume his career, which allowed him to continue to murder patients.

Being a doctor provided Shipman with means and opportunities to murder. “He could write orders for opiates,” Yorker says. “[And] he made home visits. We believe that the number of healthcare serial killings that happen in homes is vastly undetected.”

Shipman launched a solo practice in 1992, which Yorker thinks also made it easier for him to kill without raising suspicion.

Many of Shipman’s victims were elderly, though the official inquiry noted that most were generally healthy. As a doctor, Shipman could falsify a natural cause of death on the death certificate. He sometimes changed victims’ medical records to back up his claims.

Shipman killed more frequently between 1992 and ’98, claiming at least 143 victims. Yorker says an increasing murder rate is common for healthcare serial murderers.

“What happens is, they may just kill a patient here and there, but then when they realize they’re getting away with it, that emboldens them,” she says. “It becomes compulsive, and they start doing it more and more.”

In March 1998, another doctor in Hyde shared her concerns with the coroner about the high death rate among Shipman’s patients. However, a brief police investigation found no wrongdoing.

“Caregiving serial murderers…benefit from the blind spot afforded to those who care for societies’ most vulnerable,” Enzo Yaksic, founder of the Atypical Homicide Research Group and author of Killer Data: Modern Perspectives on Serial Murder, tells A&E True Crime via email.

A Forgery Revealed Shipman as a Killer

Kathleen Grundy, 81, died on June 24, 1998. She was Shipman’s patient and had apparently left behind a typewritten will naming him as her sole inheritor. However, the signature on the will didn’t match Grundy’s writing. After her daughter contacted the authorities, Grundy was exhumed, and investigators found excessive levels of morphine in her body.

Because Grundy’s will had clearly been forged, the inquiry into Shipman’s actions noted the possibility that, perhaps subconsciously, Shipman had wanted someone to stop him.

“Initially, I hypothesized that some of them got so brazen that they might want to get caught,” Yorker states. “However, after everything I’ve studied and…as I’ve looked at [our database], I now believe that when healthcare serial killers get sloppy, it’s more out of their astonishment that they haven’t been stopped so far.”

“Then they start pushing the boundaries, like writing a will,” Yorker says. “And that’s when they get caught.”

Harold Shipman’s Legacy

Shipman was arrested for Grundy’s murder on September 7, 1998. Police conducted a more in-depth investigation of deaths among his patients and charged him with murdering 15 women between 1995 and 1998.

Shipman maintained his innocence, but was found guilty of all 15 murders in January 2000. He received 15 life sentences.

Even post-conviction, Shipman never explained his actions or gave authorities a full list of his victims. Though the official inquiry concluded he was definitely responsible for 215 murders and linked him to a total of 284 deaths, a lack of evidence meant they couldn’t reach a conclusion about Shipman’s involvement in dozens of patient deaths.

Yaksic says it’s often “impossible to uncover the full scope of a caregiving serial murderer’s actions.”

On January 13, 2004, one day before he would have turned 58, Shipman hanged himself with a bedsheet in his prison cell at His Majesty’s Prison Wakefield in Wakefield, West Yorkshire.

Two decades have passed since his death, but Shipman remains a stark example of the risks posed by medical serial murderers.

“It’s too easy” for them to kill, Yorker says. “It can be months between killings for garden variety serial killers, where a healthcare serial killer can knock off five patients in a day.”

Related Features:

When Healers Become Killers: Why Some Nurses and Other Medical Workers Murder Their Patients

Charles Cullen, Niels Högel and Others: Inside the Minds of Serial Killers Who Worked in Health Care

When People with Disabilities Are Abused by Their Caregivers and No One Is Around to Help