When New York Times journalist Pagan Kennedy began researching the origins of the rape kit, she uncovered an unexpected mystery: Martha “Marty” Goddard, activist, rape survivor, and the woman who helped develop and distribute one of the first rape kits, seemed to drop off the map and disappear from society. What Kennedy learned was the toll Goddard’s efforts took on her mentally, physically, financially and socially.

A&E True Crime speaks with Kennedy, author of The Secret History of the Rape Kit: A True Crime Story, about Goddard, a tireless victim’s advocate who volunteered at a crisis hotline and used her status as an executive at the philanthropic Wieboldt Foundation to open doors, gather data about sexual assaults and distribute a tool that would change the world of sexual-assault forensics.

Was the rape kit invented by Marty Goddard?

It’s complicated because there were a lot of experiments with rape kits in the early ’70s. There were some very bad ones created in the beginning. Exactly who did what is still a bit murky. But we do know that Marty Goddard, using her nonprofit, trademarked a kit under the name of Louis Vitullo, who was a police officer in the Chicago Crime Lab. All the evidence I found suggested that it was a political decision she made at that time to get the buy-in of the men who were in control of the process—not just in the police department, but the politicians.

She pulled together the funding, she organized the training. You had to train hospital workers and crime lab workers and police officers to think about evidence in a new way. But it’s clear that Louis Vitullo created the prototype and certainly contributed a lot.

What was Marty’s ultimate goal for the kit?

She wanted to get it into every hospital in Chicago—and ultimately pushed for making a nationwide system. She also had to change the culture… She wanted this to be a new kind of evidence system, meaning that the police would not be allowed to pre-judge the person who accused rape.

In the early ’70s, when she started working on this, there were police handbooks that said many, or most, women who quote, unquote, ‘cry rape’ are lying. The attitude was that you didn’t have to listen to the victims.

Part of building the system was building a new way of looking at sexual assault as a crime you could solve, and one in which you actually had to treat the survivors with respect.

What do you think drove Marty?

She became aware of the hidden epidemic of child abuse and sexual assault in the early 1970s. It was right there in plain sight, but nobody was seeing it.

At the time, marital rape was legal, and a 13-year-old who was trafficked for sex would be called a prostitute and sent to juvenile hall. The whole way people thought of sexual assault and child abuse was very different back then.

Volunteering at a hotline for what they called ‘runaway teenagers’ at that time, she listened to the stories these kids told her about living on the street. She realized they hadn’t run away to be hippies, which was what everybody thought at the time. These kids were telling her they had run away from sexual assault in their families.

She was appalled at the scope. She also had the luck of being there right as an anti-rape movement was starting around the country. While other people were out in the streets screaming at the cops, she was fascinated with diagnosing why the system was broken and trying to figure out ways to fix it.

One of the things she landed on was: Everybody says there’s no evidence of sexual assault, but what if there is evidence? What if we could make evidence exist? That would change the conversation.

How do you think Marty would feel about how rape kits are used today?

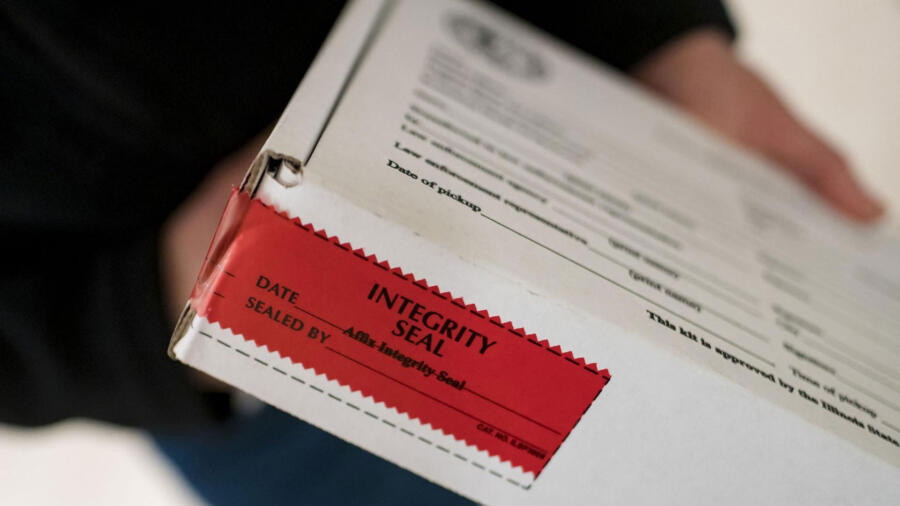

One of the shocking things I discovered is that the rape kit hasn’t substantially changed in the last 50 years. It’s still a paper box. It’s still not standardized [from state to state], which is something she would really hate, although there are people working now to create a universal standard for the United States.

The other thing is when she and other people of the early ’70s were working on this science, it was a world of rotary phones and everything was on paper, so [the kit] was designed for that world.

DNA identification hadn’t been invented yet. A lot of the methods now used in forensics just didn’t exist. Now digital evidence comes up in a lot in sexual assault cases, like text messages or videos.

Are there any groups around the country you feel are making progress in reducing, or at least not adding to, the existing backlog?

Thanks to great organizations like End the Backlog, and a lot of survivors and others who raised our consciousness about the backlog, it’s now less of a problem. It’s not like every kit has been tested, but it’s very much more on people’s radar now.

But there’s another problem that we haven’t figured out yet: It’s hard for people access the system. Think about all the rape kits that are never filed. It’s a really hard process to file this evidence—there are so many people who aren’t able to do it. Again, it varies state by state, but typically the survivor has to find and drive to a hospital that can do a forensic exam, and once they’re there, they might have to wait eight hours in the ER. The exam itself can take as much as five hours.

Imagine somebody who doesn’t have a car, or who has small children and doesn’t have childcare, or has the kind of job where they can’t take off one or two days for this process.

There are some interesting ideas out there, like mobile units where the forensic nurse comes to the survivor, and telemedicine.

I don’t have the answer, but I think there are ways we could make this process accessible to everybody and less of a burden. If we could do that, [maybe] we could get three times the amount of kits filed that we have now. We would have so much more data, so if there’s a serial predator, you could see that DNA showing up in multiple kits. Or if somebody’s innocent, and has been wrongly accused of assault, the chance that they would be convicted would plummet.

What do you hope Marty’s long-lasting legacy will be?

I hope [her story] will inspire people to think about…changes that can be made. She’s a real advertisement for getting into the weeds and understanding exactly how the system works and where it’s going wrong and where you can intervene.

Marty Goddard and so many activists of the ’70s created a new norm. Every survivor is entitled to go to a hospital and get a forensic exam and file their evidence and have that evidence tested.

Related Features:

Frances Glessner Lee: The Mother of Forensic Science