In April 2004, computer analyst William “Bill” McGuire and nurse Melanie McGuire seemed to be happily married. They shared two young sons and closed on their first house on April 28. Then Melanie told friends and family that Bill attacked her early on April 29 before storming out of their apartment in Woodbridge, New Jersey. The next day, she went to family court to get a restraining order against her husband.

In the Chesapeake Bay on May 5, May 11 and May 16, 2004, a man’s dismembered body was found inside three matching suitcases. Later that month, Virginia Beach police identified the victim as Bill McGuire.

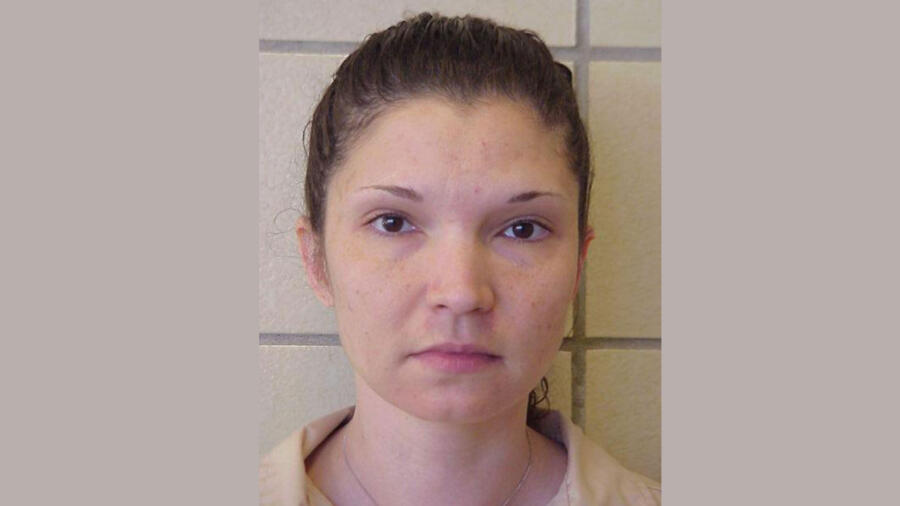

In the fall of 2004, New Jersey took over the murder investigation from Virginia. Melanie, then 31, quickly became the prime suspect. Here’s how she was revealed as the “Suitcase Killer” and where she is today.

Melanie McGuire’s Means and Motive

Melanie was a respected nurse at a New Jersey fertility clinic, but her workplace also provided a potential motive for murder—she’d been having an affair with Dr. Bradley Miller, a partner at the clinic. The pair had discussed leaving their spouses to start a life together. Court documents reveal that authorities found evidence Melanie was concerned about expenses and custody issues if she divorced Bill.

A medical examiner in Virginia, finding two .38-caliber bullets in Bill’s body, determined that gunshots to the head and chest had killed him. New Jersey police learned Melanie had purchased a .38-caliber handgun in Pennsylvania on April 26, 2004, though investigators couldn’t locate this weapon.

A computer expert unearthed several suspicious searches conducted on the McGuires’ shared computer. These included “undetectable poisons,” “how to commit murder” and “chloral hydrate.”

Inside Bill’s car, which had been abandoned in Atlantic City, police found a vial of chloral hydrate. On the last day Bill was seen alive, a prescription for chloral hydrate was sent to a pharmacy close to the McGuire boys’ daycare. The prescription came from Dr. Miller’s prescription pad, which Melanie had access to. The name on the prescription matched that of a fertility clinic patient.

On June 2, 2005, police arrested Melanie for her husband’s murder.

Theory of the Crime

Melanie’s trial began on March 5, 2007. The prosecution claimed she’d drugged Bill with chloral hydrate, perhaps in a glass of wine, before shooting him.

Dr. Robert Powers, a forensic toxicologist and associate professor at the University of New Haven, tells A&E True Crime that the amount needed to render Bill unconscious could go unnoticed in an alcoholic drink.

Post-mortem testing didn’t reveal chloral hydrate, but it wasn’t a substance the Virginia lab regularly looked for. “Chloral hydrate’s a really unusual toxin,” Powers, who was not involved in Melanie’s trial, explains. “Not a lot of labs would pick it up.”

A forensic expert at the trial said Bill’s corpse had been cut with a knife and a reciprocating saw. According to the prosecution, Melanie did this in a bathroom in the couple’s apartment. Given her slight build, prosecutors said she likely had an accomplice. No accomplice was ever charged, though authorities concluded it wasn’t her affair partner.

The prosecution also asserted that Melanie, possibly with her accomplice, wrapped Bill’s body parts in garbage bags and placed the bags in suitcases that were thrown into the Chesapeake Bay. An expert testified that garbage bags from the McGuires’ apartment matched the ones containing Bill’s body. In addition, Melanie’s fertility clinic used blankets like one found with Bill.

Melanie McGuire’s Defense at Trial

Melanie’s defense team suggested Bill had been killed due to his gambling habits and argued that the entire case against Melanie was circumstantial. The defense emphasized that, over the course of multiple searches of the McGuires’ old apartment, crime scene investigators found no blood or other evidence to back up the prosecution’s claim about how Melanie killed her husband.

However, this lack of physical evidence isn’t “beyond belief,” Michael Mears, a professor at John Marshall Law School and an experienced public defender, tells A&E True Crime. “It’s not unusual for a well-planned murder to [include] preparation. I had a client who used industrial-strength [plastic wrap] to line the floor of his office before the murder took place.”

“Absent eyewitness testimony or a confession, almost all evidence is going to be circumstantial,” Mears adds.

Crime scene investigators did find particles of Bill’s flesh on the floor of his car, which the media described as “human sawdust.” Prosecutors said Melanie transferred these particles to the car after the dismemberment. She’d told her lover she moved Bill’s car in Atlantic City late on April 29 in order to leave him stranded, so she’d admitted to being in the vehicle.

The Suitcase Killer’s Conviction and Sentence

On April 23, 2007, the jury found Melanie guilty of murder, desecrating Bill’s remains and unlawful possession of a firearm. She was also convicted of perjury for her testimony to obtain a restraining order against Bill. But the jury found her not guilty on multiple counts of trying to misdirect the investigation and possessing medication without a prescription.

She received a life sentence on July 19, 2007.

Melanie maintains her innocence, but her attempts to appeal the conviction or get post-conviction relief due to inadequate legal representation were unsuccessful. She isn’t eligible for parole until May 20, 2073, when she’ll be 100.

Melanie McGuire’s Life Behind Bars

The New Jersey Department of Corrections lists Melanie under her maiden name, Melanie Slate. She’s incarcerated in the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility (EMCF), the state’s only women’s prison, as prisoner #000319833C. She started off in maximum security, but Dan Sperrazza, executive director of the NJDOC’s Office of External Affairs, tells A&E True Crime via email that the prison conducts yearly reviews of its inmates’ security levels.

Sperrazza adds that inmates’ housing assignments are based on their custody level.

“Cell configurations vary between units at Edna Mahan Correctional Facility, but cells can [be] single or double, dormitory and honors housing for certain individuals,“ Sperrazza says.

In 2020, The New York Times and other outlets reported that EMCF staff had been sexually abusing prisoners. The NJDOC subsequently initiated reforms.

“A Division of Women’s Services was established in 2021 and assists in broadening resources and maximizing reentry efforts, while also ensuring compliance with federal PREA [Prison Rape Elimination Act] standards and sexual safety policies, training and practices,” Sperrazza says.

In June 2021, the state decided to close EMCF and build a new women’s prison, though that new facility will not open before 2027.

In addition to standard indoor and outdoor recreational activities at EMCF, a new prisoner program is Perceptions, a newsletter by and for inmates that the NJDOC posts online. According to Perceptions, Melanie has joined an advisory group for prison reform, co-runs a meditation group and has tutored prisoners in GED and ESL classes. In June 2023, she was commended for being charge-free while in custody, meaning she’s avoided altercations and other infractions.

Melanie pens health advice columns for Perceptions, as well as more personal pieces. She still hopes “to get home and care for my parents before they die,” and wrote, “I have no contact with, or knowledge of, my sons. I mourn their loss like a death.”

On the day Melanie was found guilty, The Star-Ledger reported that Bill’s sister said, “Melanie has left her two children without a father or a mother.”

Related Features:

Stacey Castor and Other Women Who’ve Gone to Great Lengths to Kill Their Husbands

The Nancy Brophy Story: Killing a Husband Goes From Fiction to Reality

Did ‘Killer Sally’ Sally McNeil Murder Her Bodybuilder Husband In Self-Defense?

How Sherra Wright Orchestrated the Murder of Her Ex-Husband, NBA Star Lorenzen Wright