This website may someday be brought to you by former prison inmates.

With the demand for web developers projected to grow 27 percent by 2024, some prisons see tech training as a promising new way to help prepare inmates for a successful life on the outside. The programs face many more challenges than traditional classes that teach inmates general maintenance or furniture making. But advocates say the payoff will be worth it as inmates enter in-demand professions and have the chance to make substantially more money than they might doing manual labor.

"Coding is the future," says Natrina Gandana, program manager at The Last Mile, a start-up teaching coding at California's San Quentin State Prison. "We're combining skills and training for a growing market. Being able to learn something challenging and cutting-edge and new is a lot of the appeal, but also the idea of getting a good job after incarceration."

WATCH: Binge all of Season 6 now, no sign in required.

Unlike some other vocational programs traditionally found in jails and prisons, computer coding can require inmates to possess foundational skills and qualifications such as a high school diploma or GED. Students must be willing to focus on an intense learning challenge, and teachers must be patient and qualified.

Applicants for these programs are carefully screened. To participate in Last Miles's Code.7370 program, which began in October 2014, applicants must have at least a GED and are required to submit records of behavioral history, write a personal essay, take a logic test, and agree to an interview.

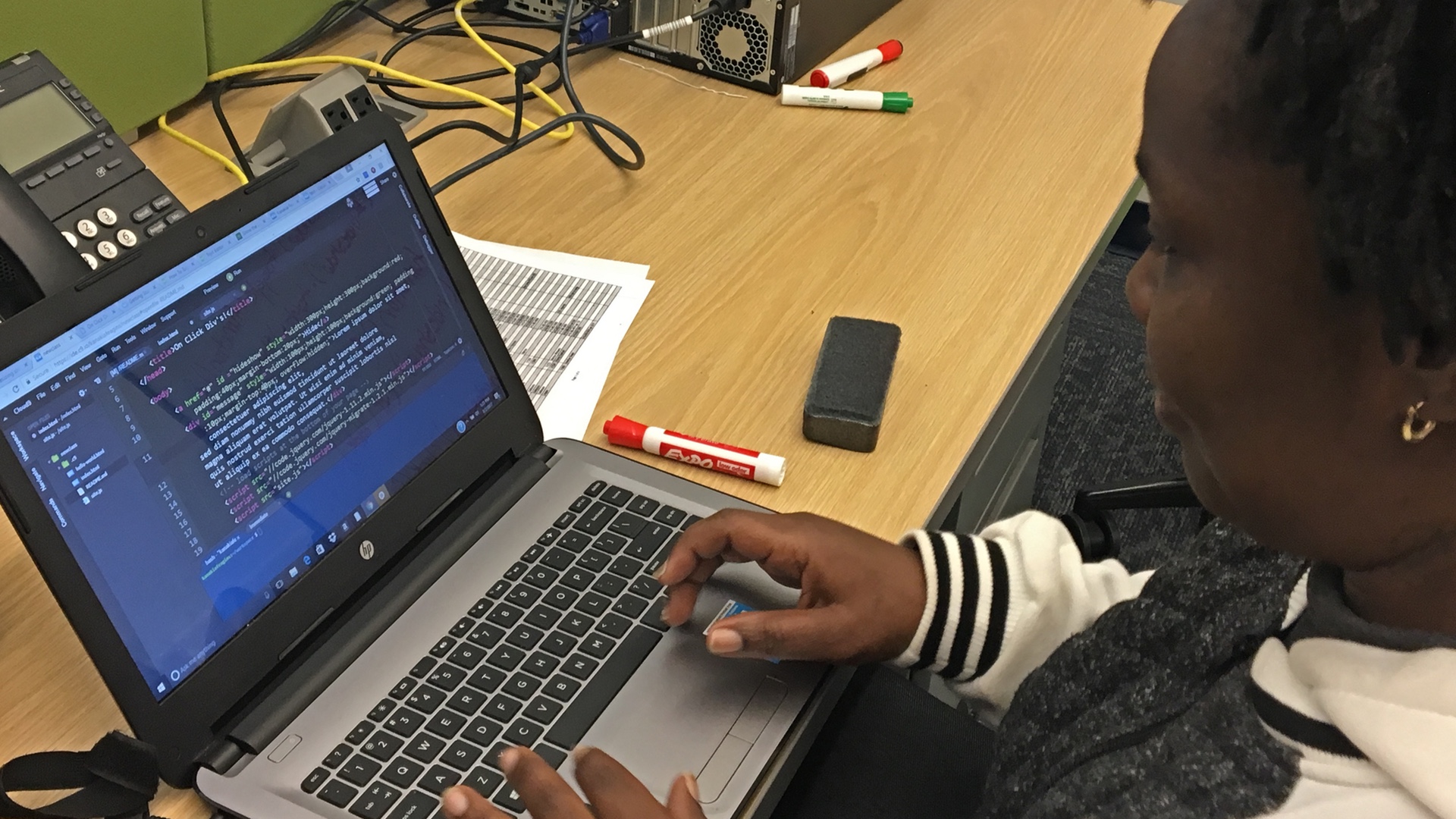

The program is taught in two six-month sessions in which 25 students attend class four days a week, eight hours a day. Students learn HTML, JavaScript, CSS, and Python, as well as web and user experience/user interface (UX/UI) design, among other skills. But there's another hurdle: students have to learn without the benefit of Internet access. They rely instead on a secure local area network server that hosts the curriculum, some of which is donated by partners.

Making a Match: Training with a Purpose

As with all prison education programs, the prime goal is to help inmates become employed and avoid a repeat prison stay. (And recidivism is a very real problem: a 2014 Bureau of Justice Statistic study found inmates released from state prisons have a five-year return rate of an astonishing 76.6 percent.)

"When you ask men coming out of prison what's the most important thing to their success in the community, about 90 percent of them will tell you it's getting a job," says Mike Thompson, director of the Council of State Governments (CSG) Justice Center, a national nonprofit that serves policymakers at the local, state, and federal levels.

But the odds usually are not in their favor.

"The challenge is oftentimes they don't have a high school or post-graduate degree," Thompson explains. "They don't have any marketable job skills. Even if they had job skills picked up in prison, they don't match what people are actually looking for in that community. They have a criminal record. This is not an easy group to connect to a job."

Ann Jacobs, director of the Prisoner Reentry Institute at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, says part of the problem is that prison vocational training programs are often focused on preparing people for jobs that won't exist when they are released, such as printing.

"One of the biggest things that encumbers the successful transition of someone from being locked up to being in the community is that they're basically cut off from access to the kind of technology that's the price of admission for most jobs," she says.

Technology may have a price, but it also offers a payoff: According to 2015 National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates (the last year data is available) from the U.S. Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics, the annual mean wage for a construction laborer is $36,550. For a computer support specialist? $55,980. Web developer? $70,660. Computer programmer? $84,360.

Make Money, Gain Experience

In addition to teaching prisoners coding skills, The Last Mile also offers on-the-job training in the form of work for paying clients.

"A lot of people who are incarcerated get 20 to 80 cents creating license plates and furniture," says Gandana. "Our students are the first ever inmates making a market wage doing development work for private clients. Coding is the future. It is a skill that is heavily sought after."

That's a double win. "This will create a savings account for them, create a portfolio. We have about five employees within our Last Mile Works program and we're starting to build our client base," Gandana says.

Because the program is so new, only one graduate has been released from prison so far. According to Gandana, he's on scholarship taking Hack Reactor classes.

The students have already gained one high-profile fan. Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg visited San Quentin in October 2015 and met with some of the student coders. In a Facebook post, he wrote. "I was impressed by their spirit to return to their communities and provide for their families, as well as the dedication of the staff to help them reclaim their lives."

The Last Mile curriculum has already been rolled out in other prisons within California: Ironwood State Prison, Chuckawalla Valley State Prison, and Folsom Women's Facility. There are plans to open at California Institute for Women within the next few months.

Training Beyond the Bars

Jonathan Moore, CEO of Baltimore-based digital startup Rowdy Orbit, is following The Last Mile model by teaching a variety of coding skills to people with criminal backgrounds. The first 34-week course started in November 2016.

"We start work on front-end web development and now we're moving towards back-end web development," says Moore. "They can crank out an HTML CSS custom site in a week or two."

In addition to attending classes from Monday to Wednesday, students participate in a paid internship with outside clients, where they apply their new skills to build up their resumes and portfolios. "Now they're one foot into the industry, says Moore.

Although the classes are free for students, the for-profit company — which is currently funded by grants and by Moore himself — makes money in student placement, essentially acting as a recruiter for local companies. Rowdy Orbit also obtains freelance opportunities and takes a cut for managing projects from start to finish.

"We want to be able to employ students with entry-level positions [as developers] within companies."

Class sizes are small — the program started out with 12 people and now down they're down to five. Of the remaining students, all are working part-time doing development work. The goal is to get them all full-time jobs once classes end in June 2017.

Success Story: An "Addiction" to Coding

40-year-old Kanakia Feagins is one of the students who has stuck with the program. A straight-A student in high school, Feagins became a Certified Nursing Assistant (CNA) after graduation. But a boyfriend was a drug dealer and he introduced her to cocaine. She liked it. A lot. Soon Feagins starting robbing for her habit and eventually started dealing drugs herself. (She admits she was a pretty bad dealer, though: She was caught by an undercover cop her first day, and ultimately lost her job. "I didn’t even have [the drugs] in my hand more than 20 minutes," she says.)

Feagins bounced in and out of jail for more than half her life — at one point getting arrested five times in one week. She estimates she's served a total of seven years behind bars. But that desire to learn never left. After her last stint in 2016 (she served 45 days on an old theft charge), she went to Goodwill Industries and took a basic computer course. When she completed it and expressed a desire to further her education and keep busy, she was introduced to Moore.

Of Rowdy Orbit's coding program, she says, "I love that I can use my creativity. I enjoy building things and using my hands."

Feagins recently landed her first freelance client and wants to continue with the program, do side projects, and eventually introduce coding to others. "There are some great minds out there," she says. "Anybody can change if you have some kind of help or push in the right direction."

Aside from learning tough coding languages, the program does come with another non-technical challenge: there's only so much time in the day. Feagins says she often becomes so focused on her work that she finds herself stretched thin at home. "Coding has become one of my addictions," she says.

That may be why the more than 50 percent drop-out doesn't surprise Moore: he knows it’s tough. Some students needed to work full-time to get money right away. Moore and Feagins both acknowledge that coding isn't for everyone.

Even for those who don't finish the course, the experience can have the benefit of making participants feel empowered in new ways, especially for some minorities, Moore says. He wants them to "understand that black and brown people have a history in technology."

Moore says Rowdy Orbit has started putting together their second class, which will have 40 to 50 students.

Digital Opportunities, No Math Required

Another organization helping formerly incarcerated people with job placement is the Center for Employment Opportunities (CEO). The nonprofit helps more than 5,000 returning citizens annually, including more than 2,500 job placements in fields including construction, retail, and food service.

While the company is exploring technology training, it is already moving in a digital direction. In December 2016, CEO launched a pilot program with VICE Media (disclosure: A+E Networks owns a stake in VICE Media) providing CEO participants with full-time paid internships to learn skills necessary to land a job in media, including video production and work on digital media channels.

Five returning citizens will be selected for the six-month paid project after an application process that includes multiple interviews.

According to VICE, the goal is to "help provide those with little to no college or workforce experience with the tools and skills needed to succeed in the media industry."

Straight tech jobs may still be in the future, but Will Heaton, director of policy and public affairs at CEO, says education and prior work experience can present barriers.

"Oftentimes they're not at a point when they come to CEO where they're prepared or able to work in a job that's more technologically-oriented," Heaton says.

Filling a Need Close to Home

Training programs can also benefit local communities.

The Michigan Department of Corrections offers the Computer Service Technician Program at two of its prisons: the G. Robert Cotton facility in Jackson, and Gus Harrison facility in Adrian. The program, which started in the spring of 2016, is delivered by Jackson Community College and funded by a grant from the Second Chance Act. One of the grant requirements was that the prison select applicants who were paroling to Wayne County (which includes the city of Detroit).

"We determined that there were [IT] jobs expressly in the Wayne County area," says LaDean Watts-George, a department analyst in the education department for the Michigan DOC. "That was one of the reasons we selected Detroit, because of the disproportionate [technology] opportunities there."

The process was competitive: 120 students, who were required to have a high school diploma or GED, were selected from around 1,000 applications. Once students complete the program, they will receive 16 college credits.

Graduates can earn industry certifications and attain entry-level information technology jobs post-release through the prison's employment agency, The Michigan Works! Association.

According to Watts-George, a majority of the students have completed their classes and are studying to take the certification exams. A few have already taken and passed both exams. As of February 2017, one graduate of the program has been released from prison and is being assisted with finding a job.

"We hope to find some type of IT employment for [all the graduates]. Some are even talking about opening their own businesses," says Watts-George.

Of course, this path is never easy. A criminal record can still hinder a formerly incarcerated person's employment opportunities, no matter what his or her skill set.

The challenge, Heaton says, is getting the public and potential employers, "to understand and appreciate that somebody should never be defined by the worst mistake they made in their life."

Photo at the top of this article used courtesy of CALPIA and The Last Mile.